Business Week has an interesting story about recent advances in glucose meters and insulin delivery systems for diabetics. Many of the devices in the story aim to improve usability in various ways to improve patient compliance and outcomes. Proper control of blood glucose levels has a tremendous impact on a diabetic's health, quality of life and susceptibility to complications.

The market for glucose management has not escaped medical device vendors or entrepreneurs:

The audience for diabetes-management tools is large--and growing. The Centers for Disease Control & Prevention estimates that there are 20.8 million American diabetics, about 7% of

the U.S. population. According to the International Diabetes

Federation's latest statistics, nearly 194 million adults around the

world are diabetic; by 2025, according to estimates, this figure will

reach 333 million. Palo Alto (Calif.) research and consulting firm Frost & Sullivan estimates that the U.S. market for traditional diabetes monitoring

(blood testing equipment and strips that diabetics use to measure their

glucose levels) tallied $3.53 billion last year, up 12% from 2005.

"In the last several years, we've seen low double-digit growth,"

says Mona Patel, director of Frost & Sullivan's medical research

department. "Yes, there will be a saturation factor, but the number of

diabetics keeps increasing--even among children." So, Patel says, the

market for pediatric devices will grow, too.

The market is slowly growing, but the real opportunity is the poor design of conventional products made for diabetics. They are hard to use, make funny noises, inconvenient, have a medical device look that makes patients look and feel "sick", have poor battery life, and can be big and clunky.

Blogger Amy Tendrich posted an open letter to Steve Jobs on her blog Diabetes Mine, challenging Apple to bring the same design excellence they bring to consumer electronics to devices for diabetics. The Business Week story describes a design created in response to Tendrich's plea, and touches on a number of other products. (Surprisingly, no mention of DexCom's continuous glucose monitoring system.)

The (glacial) transformation taking place in diabetic devices highlights a structural problem in the medical device industry. Due to barriers to market entry, established vendors feel little pressure to create the equivalent of an iPod for diabetics. Some vendors like Medtronic have created innovative systems like the MiniMed insulin pump with real time glucose monitoring. But in order not to cannibalize sales from their conventional products line, they price the new solution at a significant premium. (Medtronic has taken a similar approach to their relatively new wireless ICDs, charging a $6,000 premium for the wireless models over products that still use induction wands that must be placed over the pacemaker. I know cardiologists that refuse to implant the wireless models because they feel it is unfair to burden the patient/payor for such a high premium.)

Payors only reimburse for technology that has a clear return on investment. They won't reimburse for a fancy (read "expensive") MiniMed pump for a patient whose condition does not require continuous monitoring and administration of insulin. Sure payors will pay more for a product with better outcomes (i.e., lower costs to the payor resulting from a healthier patient). But proving those improved outcomes - and lower costs of care - is an expensive and time consuming proposition.

It appears that Medtronic - and vendors who pursue a similar strategy - are stuck with a small subsection of the diabetic market, unless they're willing to reduce the price of the MiniMed where patients are willing to pay the difference over what their payor will reimburse for a conventional glucose management system.

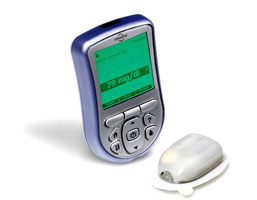

The poor comparison between conventional glucose management products and consumer electronics has not been lost on medical device entrepreneurs. Vendors like Medicom, DexCom, Health Pia, and Insulet (pictured right) are bringing better designs and technology to market. These new players will need more of a consumer electronics product strategy, rather than Medtronic's strategy for the MiniMed, if they are to succeed.

More here in a iHealthBeat story about a recent FDA continuous glucose monitoring approval for children that highlights cost and potential savings in reduced health care costs.

of their blood sugar through the devices, although other studies have

found minimal impact. Irl Hirsch of the University of Washington said

the discrepancy can be attributed to a lack of effort from diabetics,

not the sensor technology.

The glucose sensors can cost up to

$1,000, with at least $350 in monthly fees for supplies. Although some

insurers pay for them, many refuse to reimburse patients for the

devices until there is more proof that they improve health, the AP/Star reports.

UPDATE: Reader Bernard Farrell has an excellent point in the comments:

present. They don't adequately cover treatments for chronic diseases, and then

later they pay for the outcomes of poor management. There is an argument that

better designed devices will lead to better medical outcomes AND lower support

costs for the device makers. As far as I'm concerned good device design is a

win-win-win situation for patients, device makers, AND insurance companies.

Unfortunately it feels mostly like I'm shouting into the wind about this.

There are two problems I think. The first is demonstrating the hard dollar savings from well designed devices. This naturally falls on the device vendor, and is neither a quick or inexpensive task. The other problem is the tendency of device vendors to want to get a significant premium for their better designed product. A major price increase requires justification before payors will reimburse for a new "class" of device. If a vendor introduced a better designed device (with some additional features) at a slight premium, patients might be willing to pay the difference themselves - think the iPod.

Perhaps what's needed is more of a consumer electronics mindset applied to these kinds of products, rather than the conventional medical device paradigm.

I am living proof of an insurance companies refusal, well waffling in my case, to pay for new devices. I’ve been a diabetic (Type 1) for 3 short years of my 33 year life, needless to say such a drastic change for a free spirited eat anything in sight (might I add in shape athlete) has been hard to grasp. The pump seemed like a Godsend, and wireless/tubeless devices for a Geek like myself was unbelievable (I work for Geek Squad). Now after 3 months and my first shipment of pods overdue and undelivered I’m being told by Insulet Corp that my insurance wont pay. Thats right just 3 months ago there were no problems, it would supposedly cost me 230 dollars every 3 months and I was all set….now I’m down to my last 2 pods and my scheduled shipment didn’t show up so I called. I’m told there is a problem with the insurance and to wait for someone to contact me. I’m still waiting and my pod supply has dwindled to two.

The frustrating part is after 3 years of struggle. 3 years of catching every single sickness that comes into the house, or is carried into work (I have young kids so there are many). Three years of massive swings in sugar levels which we all know leads to massive swings in psychological well being. 3 years of my employer thinking Im dying due to the missed days of work and constant doctors appointments. For the first time I was on the road to recovery, Ive gained back nearly 15 pounds in 3 months of the 60 pounds I lost before I was properly diagnosed. I had missed a grand total of 3 days work in the last 4 months and that was due to malfunctioning pods.

Its all for nothing apparently, thanks to insurance companies endless hurdles and the lack of concern (or so it seems to me) from the product manufacturers Ill be left on the outside looking in. I suppose I make enough money that I could pay out of pocket for the pods but it will leave me with very little to spend elsewhere and require some sacrifices from my entire family such as giving up daily luxuries like cable TV or cutting the AC/Heat back a notch or two to make the budget work, among other things. I’m a bit disappointed to say the least and look forward to the day when diabetics are treated properly by insurance companies and offered the best solutions to their health condition on an individual basis and not with the wide net that most insurance companies cast. It seems to fall on deaf ears when I mention to them my insurance costs which total 1100 a month when you add together my contribution and my employers contribution, then factor in my employer (ultimately Best Buy owns Geek Squad) has tens of thousands of participants within the insurance companies coffers. At the end of the day some fat cat with undoubtedly perfect health decides whether or not a treatment I know works is best for me, thats just grand.

Scott, I empathize with your situation. Given the rapid increase in health care costs, payors are understandably reluctant to pay for fancy new tech when it is not clear there will be a related reduction in health care costs.

I would suggest you work with your physician to provide the clinical justification for the tighter glycemic control that is provided by a pump. Submit that to your payor with another request for reimbursement for the pump. While the convenience of a pump is great, that’s pretty much funded by the patient rather than payors.