Off Label Use

In a previous post, Medical Device System Network Install Issues, I suggested that when health care providers don't follow medical device manufacturer's specifications when installing medical device systems they were using the system "off label." This site's latest contributing author, William Hyman, provides an alternative perspective:

My interpretation of off-label use has been that it pertains to the actual use of the medical device, not the way it is set-up. Thus it isn't off-label use until it is actually used, and use here is with respect to the Indications for Use, which do not generally address set-up and configurations as opposed to what the device is for.

Therefore a set-up or installation that is different from the manufacturer's recommendations/specifications may be a modification rather than an off-label use. Other types of reconfigurations and changes would also be a modification.

Practice of Medicine Doctrine

Off label use is unregulated per the "practice of medicine doctrine," but comes with some risk management issues. Also please note that this doctrine applies to physicians, not health care provider organizations. According to Hyman:

This is more than a semantic distinction. Off-label use of a medical device, at least by physicians, is legal and unregulated. This of course does not necessarily mean it is safe, smart, or well justified. The defense of an unsafe off-label use (if necessary) would be an after the fact liability matter, not a regulatory matter. However hospitals might be wise to have their own controls on off-label uses and require appropriate justifications.

After some research, I found that there's very litte published -- by the FDA or others -- about the issue of post-market regulated device modification, especially by health care providers. Hyman delivers more:

Modifications on the other hand are, according to the FDA, a regulated activity, although the FDA's stated position, as I understand it, has been that within its regulatory discretion it does not actively pursue in-house device modifications. An important feature of regulatory discretion is that it can change without notice, and/or be exercised sporadically. One might anticipate that if all goes well the FDA will not become interested, but if something bad happens they will be interested. In that latter case they could find you out of compliance even though they had no previous interest in your activities.

The best resource I could find, besides Hyman, a paper written in 2007 by Georgia Skoumis (no longer available online), when she was a Harvard law student (relevant excerpt here). This paper confirms Hyman's assessment of the FDA's ability to regulate physicians:

The practice of medicine doctrine was articulated explicitly in the Food and Drug Administration Modernization Act of 1997 (FDAMA).5 The relevant language reads:

Nothing in this Chapter shall be construed to limit or interfere with the authority of a health care practitioner to prescribe or administer any legally marketed device to a patient for any condition or disease within a legitimate health care practitioner-patient relationship.

What constitutes a legitimate health care practitioner-patient relationship is not defined in FDAMA, and the applicable section further states that its provisions do nothing to limit the existing FDA regulatory powers.

Medical Device Modification

Skoumis also notes that the, "exact boundaries of the practice of medicine doctrine are unclear."

The exact boundaries of the practice of medicine doctrine are unclear. At one extreme, there is little doubt that a physician may use a locally-fabricated device for the care of a specific patient without federal regulatory repercussions, provided the patient gives informed consent to such use – state or institutional controls notwithstanding.6 Conversely, a physician who acquires a device or device materials through interstate commerce, fashions a non-FDA-approved device, and actively attempts to market the product to patients across state lines almost certainly violates the FDCA [the Food, Drug and Cosmetics Act].

Between these extremes there is a great deal of uncertainty. Within this gray zone lies the issue of medical device modification. When the party modifying a medical device is a regulated manufacturer, the issues are straight forward. Modifications of a device that could affect significantly the safety and effectiveness of a device, or change the device's intended use, require the submission of a 510(k) application. If you're not a regulated manufacturer, but you are a physician acting in a responsible manner (a complex and very lengthy topic we won't get into here), you are probably okay. If you are a provider organization engaged in an effort that is not lead by a physician who assumes responsibility for the consequences, your risk is considerably greater.

It should also go without saying that the "protection afforded by the practice of medicine doctrine and the custom device exemption is destroyed by the active marketing or commercialization of the modified product."

Hyman's understanding coincides with Skoumis':

Modifications [...] are, according to the FDA, a regulated activity, although the FDA's stated position, as I understand it, has been that within its regulatory discretion it does not actively pursue in-house device modifications. An important feature of regulatory discretion is that it can change without notice, and/or be exercised sporadically. One might anticipate that if all goes well the FDA will not become interested, but if something bad happens they will be interested. In that latter case they could find you out of compliance even though they had no previous interest in your activities.

Here is a relevant quote from an email received by Hyman from the FDA in 2003:

In general, the FDA has the authority over a device and any person of facility where anyone is engaged in the manufacture, preparation, propagation, compounding, assembly, or processing of a device intended for human use (21 CFR 807.20). Title 21 CFR 807.81 makes it clear that anyone introducing into commercial distribution a device, must meet the premarket requirements. Physicians, who produce or alter a device , for use within their own practice are exempted from the premarket notification requirement (21 CFR 807.65 (d)), but they are not exempted from the premarket approval requirements for [a] Class III device. Unfortunately for you, congress did not wish to extend the physician exemption to hospitals.

[...]

The bottom line is that we have no interest in overseeing anything that a hospital does. We know that it is common for biomedical engineers to make modifications. However, it is important for the facility to understand that when such changes are made, the facility is basically assuming all liability for that device. They are changing a device that has been placed in to commercial distribution. It is used on humans, and therefore is regulated under FDA authority. When, and only when, there is a problem with one of these modified devices, the agency can and will step in and exercise our authority in the interest of public health.

Be sure to read the blog post on Medical Device System Network Install Issues to get a full appreciation of the importance of this issue relative to complex medical device systems that are installed in hospital managed operating environments (i.e., networks).

Tim,

As always, it is great to read your insight into medical devices, interoperability and regulation.

I notice you mention biomedical engineers in your post, it is probably safe to assume the same applies to the IT organization of the healthcare service provider. If anyone, you know that the line between an old fashion medical device and an IT integrated medical device is becoming harder to distinguish.

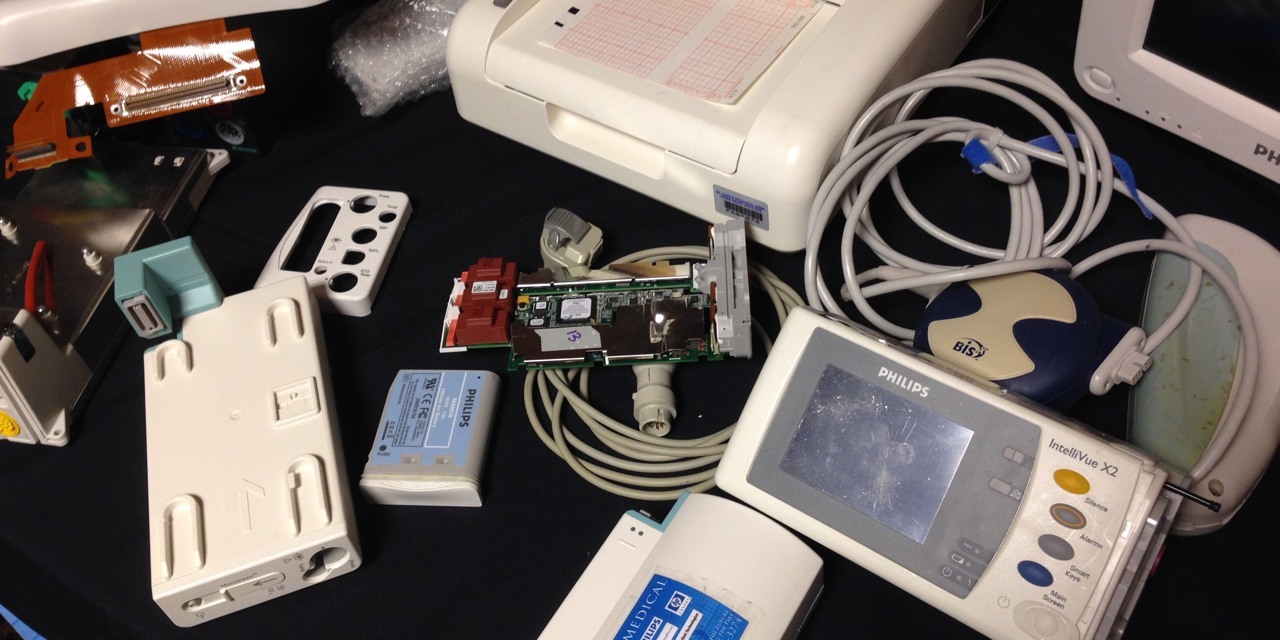

Clearly, a device sitting in a patient room such as a physiological monitor is a medical device, however when a manufacturer packages their overall system into 510(k) submission, now the servers and all those components become part of the medical device system. I would agree to a point that an acquisition workstation is a medical device and careful consideration should be given when making any changes, such as security patches.

Outside of software changes, here is where I start to get really frustrated with manufactures. Without mentioning the specific vendor, here is a current example we are dealing with. A certain fetal monitoring system uses a variety of servers located in our IT organizations data center. Recently the system went down for several hours due to a bad power supply in one of the data acquisition servers. For years we pushed the vendor to use dual-power supplies and that we would even supply them, their model of server is actually one of our adopted standard servers but is supplied by the manufacturer.

Of course the vendor said we could absolutely not add a redundant power supply to the server because they would have to re-submit for a new 510(k). That is just a flat out false statement by the vendor, in no way does adding a redundant power supply alter the intended use or impact the safety of the device. Now, if they said they would have to test it based on FDA regulations, I would at least agree that they understood the FDA rules and guidelines. As someone in IT, I know a redundant power supply is not going to negatively impact the server in any way considering we have 500+ servers configured this way.

We have other vendors who’s systems have hard coded IDs and passwords embedded in their system that are published on known hacking web sites (fact). The same vendor believes running part of their system on Windows 2000 Server is acceptable. We isolate these types of systems as much as possible to minimize the risk they pose to the organization.

However, in the case of adding a redundant power supply to a backend server, what do you do? If we add it, and six months later a fetal monitor malfunctions, is that now the responsibility of the IT organization even though in no way could that have affected a monitor located in the patient room? When you research the vendors 510(k) approvals in the FDA’s database, you find the monitors have their own approvals but ultimately roll up into a whole system.

I am not minimizing the risk these vendors have when it comes to an actual device connected to a patient, but I take exception to the security and reliability risks these vendors continue to add to a service providers overall network of systems. IEC 80001 is on the horizon, perhaps one day we will be able to gain some leverage over these risky systems or at least get vendors to cooperate.

In an ideal world, FDA regulations would incorporate blatant security risks with respect to IT systems.

Craig

Craig,

Unfortunately, manufacturers (or at least some of their employees) use FDA regulations as a smoke screen all too often.

You are correct that the manufacturer would not have to file a new 510k because you decided to put a redundant power supply in their server.

The rub for most vendors is that they would have to follow the FDA’s Quality System regulation and create a bunch of design and test artifacts that would go into a “letter to file” documenting those changes. Just the paperwork could cost upwards from $300,000.

Smart vendors write better requirements and specifications for the general purpose IT components in their systems that minimize or eliminate the burden of these kinds of minor system tweaks.

That said, there is nothing keeping hospitals from making those changes themselves - except some legal and regulatory liability. This liability is reasonably managed, but like vendors not knowing how to write requirements, most hospitals don’t know exactly what to do to mitigate that liability. The result is nobody does anything except you, when a power supply fails.