Reader Geoff T. sent this link to a story in Healthcare Design magazine on a new heart hospital at Ohio State University Medical Center. While I have mixed feelings about specialized hospitals, I was encouraged by the broad adoption of variable acuity units. For this crew, building a new hospital just like the old hospital was not an option.

Simply building a new facility would not be enough, the team realized—a change in care processes would have to accompany the changes in building structure and unit/facility design. In line with this, the traditional multiple-transfer setting—where patients were transported to different units based on the severity of their illnesses—was eliminated in favor of the acuity-adaptable/universal bed healthcare delivery concept. In this model, the required level of care is brought to patients while they remain in one room throughout their entire hospitalization.

The jargon related to this care delivery model is varied and not well defined. Terms include "flexible monitoring," "acuity adaptable," "variable acuity," and (my least favorite) "universal beds." Unlike the other terms, "universal beds" implies the ability to scale patient acuity all the way up to a full fledged ICU room. The cost to supply power, gases, suction and other infrastructure to a room for the small slice of time it will support ICU level care is considerable - and of course creating rooms like this is only practical with new construction. The rooms described in this story are in fact universal beds that can flex to provide ICU level care.

The rationale for choosing this care delivery model over conventional nursing units divided along patient acuity levels is described below:

As noted, a key attribute of the UB [universal bed] care delivery model is the elimination of multiple patient transfers to various levels of care. An acuity-adaptable room significantly reduces such inefficiencies; it also enhances patient safety, since the level of care changes rather than the patient’s location. In the typical setting, a patient transfer from an intensive care setting to a telemetry floor generally involves seven to nine staff members from various clinical and ancillary areas; it costs about $500 and takes an average of almost four hours. With this large number of staff involved, the potential for miscommunication is high and can result in medical errors. Reducing or eliminating transfers significantly decreases the potential for medication errors, lost belongings, and patient confusion or unease.In addition, the RHH [Ross Heart Hospital] was designed to minimize time spent on transfers from procedural areas to patient rooms. The procedural areas are located on the same floor as the corresponding patient care area, creating mostly horizontal connections rather than elevator transports, thus saving time and reducing the costs associated with procedure-to-recovery transfers (figure 4).

The universal rooms were also strategically designed to minimize transfers required for diagnostic tests. Rooms are large and private, and room-darkening window shades allow the performance of portable tests on the patient floors. A large number of echocardiograms and chest x-rays are now being done at bedside with the goal of increasing the portability of noninvasive testing modalities.

An overlooked cost of patient transfers is the resulting addition of one day to the patient's length of stay. Reduced transfers can translate into a significant reduction in a hospitals average length of stay (ALOS), free up capacity and minimizing the need to fill open RN staff positions.

The good news about variable acuity units is that you don't have to build a new hospital to implement and benefit from this care delivery model. Implementing variable acuity support that includes patient monitoring and ventilators - and provides a level of care just short of the ICU - requires the right medical devices, a wireless infrastructure to support those devices, new policies and procedures in each unit to accommodate higher acuity care (like titrating drugs), and training for your nursing staff. The costs are much lower as soon as you forgo flexing all the way up to ICU levels, but implementation issues are the same:

Using the UB care-delivery model does not mean that any nurse can care for any cardiac patient. Nurses, like physicians, tend to practice in a specialty they enjoy. Nursing staff specializing in a certain clinical area are generally able to provide more efficient, higher-quality care and are able to troubleshoot more rapidly because of their expert knowledge in that specialty.At RHH, like patients are aggregated on each of the three 30-bed patient care floors. One floor supports medical cardiology and vascular patients, another cares for cardiac surgery patients, and the third provides care for cardiac cath lab/electrophysiology patients. Recovering outpatient cardiac cath lab patients are intermingled with the inpatient population because their recover processes are clinically similar. Thus, instead of recovering in a busy, hectic, and crowded bay within a procedural recovery area, cardiac cath lab patients are able to enjoy the comforts of a universal room—a private room that can accommodate family members while offerin a quiet, healing environment.

Another wrinkle in supporting variable acuity units is the need for surveillance and alarm notification. Conventional central stations, war rooms, remote annunciators, hallway lights, and message panels are problematic. The big issues are cost versus alarm fatigue, and the various ways safe and cost effective care can be provided. Another issue is the physical layout of the unit. The Ross Heart Hospital adopted another innovation, decentralized nursing units.

RHH elected to place nursing documentation stations—with access to electronic patient information, supplies, and medications—in the patient rooms themselves (figure 5). Surveys maintain that nurses often work from memory when patient records are not easily available, thus increasing the chance for medical error. The decentralized stations ensure that staff use the patients’ records with every care activity and eliminate the chaos and noise associated with a central nursing station.This practice has been proven to reduce patient stress levels and facilitate healing. RHH patients state that although the unit is quite large, it is reasonably free of noise. Moreover, OSUMC believes that decentralized nursing documentation

Decentralized nursing units have many advantages, but one of the problems is that current patient monitoring systems are ill suited for this type of layout. Placing multiple central stations at each decentralized unit takes up a lot of space and is prohibitively expensive. There is one vendor who has announced a solution to the problem, but in general, hospitals will have to demand new products that better fit this rapidly growing approach to nursing units.

Here's a thought experiment for you. Look at your ADT data and figure out your average transfers per admission. Cut those transfers by 80% and apply a one day LOS per reduced transfer. Would the "change pain" of implementing variable acuity units impact your hospital? Perhaps off-load all those inappropriate admissions in your critical care areas and telemetry? Reduce the time spend in diversion? Do you have (or can you generate) demand for those new patient days? How much would that increase your revenue?

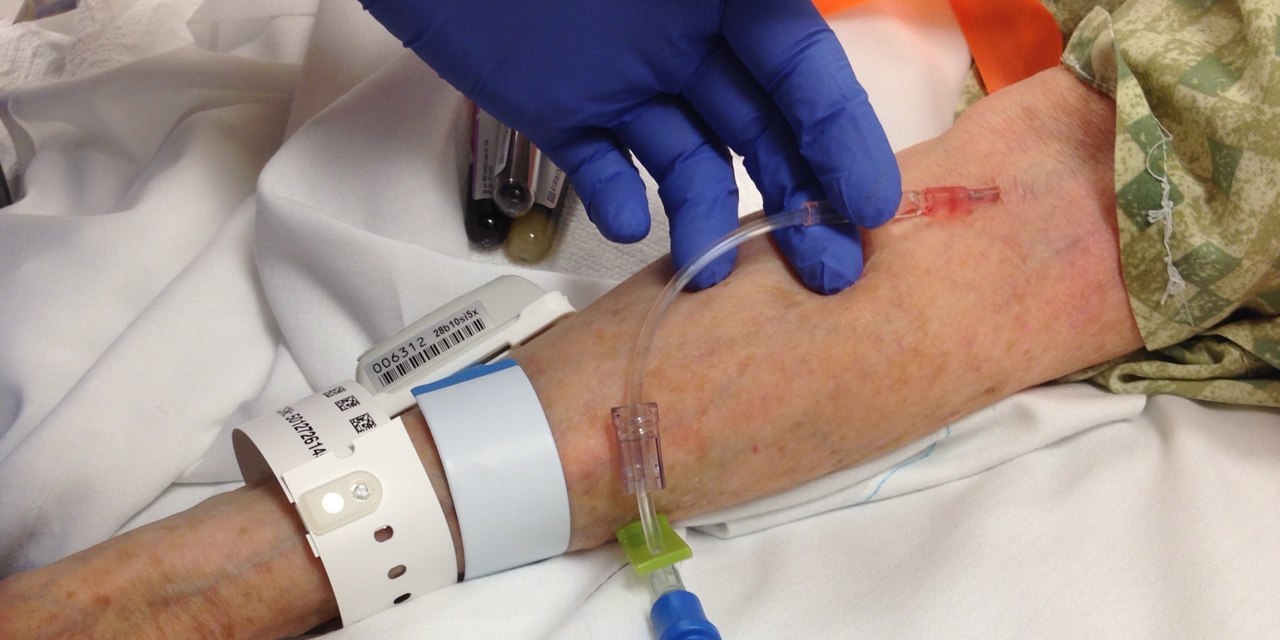

If you'd like some help with answering these questions, and perhaps taking the variable acuity plunge, let me know. Pictured right is the high acuity configuration of the new Ross Heart Hospital's acuity adaptable rooms.

Can I be given a tel. # to discuss what you could potentially do for one of my clients?