On August 25, 2016, Muddy Waters Research (MWR) published a report titled, MW is Short St Jude Medical, claiming that St Jude Medical's (STJ) connected cardiac rhythm management products should be recalled due to exceptionally poor data security. MWR claims:

- The effected products include the Merlin.net Patient Care Network, Merlin@home remote monitoring gateways and implantable pacemakers and ICDs that use wireless radios to communicate with Merlin programers (used by providers) and Merlin@home gateways located in patient's homes.

- These products collectively represented 46% of STJ's 2015 revenue.

- MWR further claims that the recall and remediation of the data security problems are estimated to take 2 years to complete, and that

- STJ's revenue will be negatively impacted by the recall.

Consequently, MWR has shorted STJ stock in a bet that their actions will cause STJ's stock price to fall. This appears to be the first example of a data security vulnerability being used to short a company's stock (more on this below).

Who Is Behind this Report?

MWR (Wikipedia profile) is a privately held due diligence based investment firm that conducts investigative research on public companies in which it then takes investment positions that reflect their research findings. In the past MWR investigated fraud and corruption in US traded public companies that are often based outside the US. The STJ report appears to be MWR's first attempt to leverage the disclosure of data security vulnerabilities to move markets.

The MWR report is based on research completed by MedSec, a vulnerability research and security services provider for medical device manufacturers and health care providers. The research is part of an 18 month effort in which a variety of medical device systems were tested.

MWR reports that they were approached by MedSec with their research which has been validated by MWR.

Motivation for the Report

MWR is in the business of leveraging deep research for financial gain. Regardless what one thinks about the moral ethics involved in this practice, it is legal. The market provides incentives to firms like MWR to find and disclose bad actors that may have avoided disclosure as a consequence of corruption, graft or a successful avoidance of law enforcement. In this report, MWR suggests STJ has been negligent in not addressing blatant data security vulnerabilities.

MedSec was founded 18 months ago by a team of researchers in Miami. They immediately undertook an effort to research a set of medical device systems, including the STJ system.

In an interview, MedSec CEO, Justine Bone described the following rationale for the decision to disclose:

- MedSec researchers found that the STJ products were exceptionally lax in their data security when compared to the other manufacturer's products they investigated over the past 18 months (see the supporting table comparing STJ to 3 other manufacturers in the report).

- STJ has a reputation among the data security researcher community for ignoring and not fixing vulnerabilities, starting with Barnaby Jack's experience with STJ, and past security vulnerability investigations by Homeland Security and FDA.

MedSec felt a disclosure to STJ would not result in any product changes or be disclosed to patients. Rather, they took a path to shake things up and at the same time assure some disclosure to the public.

Another important factor mentioned by Bone is that MedSec is a commercial entity and would like to recover some of their research costs. Clearly, the notoriety produced by this disclosure also raises this 18 month old startup's profile within the data security market.

Key Claims

According to the report, the following common data security defenses are missing from the STJ products:

- Authentication for devices wishing to access the network or communicate with implanted devices,

- Encrypted protocols, communications and software,

- The use of anti-debugging tools, and

- Anti-tampering mechanisms built in to the STJ products.

The communications protocol used by the implanted devices, Merlin@home, Merlin programer and the Merlin.net Patient Care Network lacks any authentication and encryption (other then the patient data – STJ apparently has HIPAA covered in this respect). From the report: "Attackers who can reverse engineer the communication protocol can access and impersonate parts of the ecosystem, including the Cardiac Devices [i.e., implanted devices]."

The embedded system devices, Merlin@home and the Merlin programer, lack basic anti-tampering mechanisms. For example the chips in the Merlin@home are not obfuscated to remove the identification of chip manufacturers and model numbers. Another shortcoming noted was the use of a removable hard disk drive in the Merlin programer, which could be removed and attached to a PC to facilitate hacking. MedSec noted that multiple STJ competitors obfuscated their hardware and used some "proprietary" chips to protect their devices from reverse engineering.

The software in the Merlin@home device, extracted from the labeled Samsung flash memory chip, was not encrypted. Patient data was encrypted. Besides accessing the Merlin@home device software via the memory chip, MedSec was also able to access the software by getting root on the device and copying files to the USB port. A forth access method was mentioned but redacted.

Once the user has root on the Merlin@home device, additional network information is accessible, including:

- The toll-free access number for the Merlin network. (The Merlin@home devices connect to the Merlin network either through a phone line connection or a 3G token.)

- The User ID and Password for the Merlin network. These credentials are static, i.e., they are used to authenticate all Merlin@home devices on which MedSec got root.

- STJ server IP addresses (in older device versions),

- SSH keys (in older device version). SSH keys are the “private” keys in a “public/private” key pair system.

MedSec is prohibited by law from testing whether these SSH keys are still in use by STJ’s network. In later versions of software, the SSH keys have been changed. If the keys are still in use, they could assist an attacker with a network-based attack.

Using the above vulnerabilities, MedSec claims to have developed and tested two exploits on STJ implantable devices: crashing or misconfiguring the pacemaker by fuzzing, resulting in pacemaker behavior that would likely result in patient injury or death, and running down the pacemaker battery resulting in failure. All of the pacemakers used in the MedSec research have been bricked.

Also included in the report is a somewhat redacted table showing a comparison of data security features of the STJ devices and 3 other manufacturers' systems. MedSec has announced that they will be releasing additional research on some of the other medical device systems they have tested in the month of September.

Proving the existence of these shortcomings will require the release of the complete report (not the publicly released redacted version) and/or the validation of the research by a third party. The University of Michigan Archimedes Center for Medical Device Security has made an incomplete effort to validate the MedSec research (more below). And one supposes that the FDA or Homeland Security are validating the research.

For those interested in a primer on pacemaker security issues, check out this lecture by medical device data security expert and academic, Kevin Fu.

The Case for Recall

The objective of the MWR report is to cause a meaningful reduction in STJ's stock price. Two of the most direct paths to dropping STJ's stock are a product recall and causing the merger with Abbott to fail. MWR laid out their recall strategy in their report starting on page 18.

At this point it does not appear that STJ is going to voluntarily recall the devices described in the MWR report. MWR's next objective is to cause FDA to force a recall. MWR builds their case for a recall on the FDA's draft guidance, Postmarket Management of Cybersecurity in Medical Devices, published in January, 2016.

For many years, little attention was paid to embedded system medical device security with manufacturer's rhetorically asking, "Why would anyone want to hack my medical device?" And indeed, most embedded system medical devices offer little motive for hacking besides recognition (Barnaby Jack, Billy Rios and others) or murder. The implied rationale was that because there is no direct profit motive, there's little likelihood of a cybersecurity attack, and thus little reason to expend much effort on data security. While the foregoing is true, there are reasons to secure devices even if they are of no interest to cyber criminals.

The FDA draft guidance on postmarket cybersecurity gets around the above argument by framing risk management in a different way. Focus is shifted away from hacker motivation and the likelihood of an attack to devices essential clinical performance. From the draft guidance:

Essential clinical performance means performance that is necessary to achieve freedom from unacceptable clinical risk, as defined by the manufacturer. Compromise of the essential clinical performance can produce a hazardous situation that results in harm and/or may require intervention to prevent harm.

With this definition, the question, "Why would anyone want to hack my medical device?" becomes moot. Risk management is now based on 1) The exploitability of the cybersecurity vulnerability, and 2) The severity of the health impact to patients if the vulnerability were to be exploited. The draft guidance deems a vulnerability with high exploitability and catastrophic impact if exploited an uncontrolled risk. Uncontrolled risks must be reported to the FDA unless the manufacturer implements changes to lower the risk level and notifies users within 30 days of learning of the vulnerabilities.

MWR's case for a recall hinges on the vulnerabilities in the data communications protocol described above and the difficulties described in the MWR report that STJ would face in making those changes. The MWR report contains considerable detail supporting their case for a recall, including relevant precedents pertaining to the Hospira Symbiq pump and Guidant pacemakers (the Boston Scientific example benchmarks the potential financial impact of a recall but is a result of Quality System deficiencies rather than lapses in data security).

On August 26, 2016 it was reported that the FDA, along with Homeland Security are actively investigating the claims made in the MWR report. MWR has also reported that they provided a version of the report to the FDA for their review.

Analysis

The MWR report claims are very credible. STJ would not be the first or only medical device manufacturer to approach data security in the way alleged in the MWR report.

The responses from STJ make no specific assertions in their defense against the claims in the MWR report other than a few select assertions made in response to claims first made by MWR. These defensive assertions refute mistakes made in MWR's report, such as the transmission distance of pacemakers (50' in the lab, but much shorter when implanted due to the signal attenuation caused by water in the human body), and the behavior differences between unconnected pacemakers versus pacemakers connected to simulated leads and a patient's heart. The STJ response seems weak and shrill.

In the absence of validation testing of MWR's claims, we are left with PR spin and perceptions. Validation testing is likely being done by STJ (unless they already know MWR's claims are true), the FDA and Homeland Security (or some other agency with more data security experience than FDA, like NIST), and perhaps third parties like the University of Michigan Archimedes Center for Medical Device Security and/or other independent researchers. To be successful, MWR does not need to prove their claims in a public forum, they need to force a recall.

To force a recall, there must be 1) easily exploited vulnerabilities that 2) result in a situation where patients could suffer injury or death. Assuming MWR has accurately captured the exploitable vulnerabilities that make hacking a STJ pacemaker relatively easy, the question is whether they can demonstrate credible risk to patients. MWR claims to have succeeded with two attacks, crashing the pacemaker and running down the battery. If FDA can validate both these things are true, it is game over and MWR wins.

There have been many questions regarding potential reasons why FDA might not issue a recall:

- Unlikely threat: this goes back to the perennial question, “Why would anyone want to hack my medical device?” The underlying position is that data security is not needed because there are no incentives for bad actors to take advantage of these vulnerabilities. This is bad policy and has been rejected by FDA, most specifically in their draft guidance on postmarket cybersecurity.

- Too disruptive or expensive for STJ: the FDA's penultimate concern is patient safety, not manufacturer profitability. The MWR report referenced a number of examples where the FDA lowered the boom on manufacturers. Besides those, there are numerous examples where FDA got consent decrees limiting manufacturer's ability to manufacture and ship product for extended periods of time (Physio-Control, Baxter and Medtronic come to mind). While crony capitalism has become an uncomfortable part of the health care industry as a whole, it has yet to penetrate the FDA.

- Preemption: To suggest that because the FDA already approved or cleared the various STJ components mentioned in the MWR report the FDA can't or won't issue a recall is wrong. Preemption is not a shield against negligence (as charged by MWR), nor does it apply to evolving regulatory requirements like data security. Much of the FDA's guidance on cybersecurity was published since the last approval for Merlin@home in 2012. For more on preemption, see this Riegel v Medtronic preemption case blog post.

- Inability to show device failure: At last, we see a legitimate justification for not recalling. If the data security vulnerabilities are relatively easy to exploit, the FDA may not or may not feel compelled to have proof of a successful attack that would result in patient injury or death to justify a recall. When the researcher has access to the device to be hacked, it is almost assured that they will eventually construct a successful attack, that's just the nature of software based devices. It appears that MedSec mistakenly misinterpreted the Merlin programer screen showing leads-off alerts to indicate a crashed device, however this does not mean that MedSec was unsuccessful in attacking the STJ pacemakers.

The scope of a recall would include a ship-hold impacting all implantable devices that include radio communications, the Merlin@home, Merlin programer and Merlin.net.

The time required to mitigate the vulnerabilities could be substantial. For example, if the software in the Merlin@home device interleaves the communications protocol software with numerous other portions of the software (rather than the industry best practice of separating functionality into separate software modules or objects) and thus necessitating a review and modification of all or most of the Merlin@home software, a two year timeframe is a distinct possibility. The potential for any recall of less than 12 to 18 months is unrealistic. The product development process required by the FDA Quality System and the verification and validation testing required for Class III medical devices likely precludes any shorter time frames.

Bottom line: those with a financial position in STJ are likely hedging their bets.

Given the flack MedSec has taken for the method of the STJ disclosure and their attempt to monetize the found vulnerabilities, it will be interesting to see how they handle the promised September report on the other research that's been conducted over the last 18 months.

Chronology

The following is a chronology of the events and reporting that have unfolded in response to the MWR report.

August 25, 2016

MWR drops their report, Muddy Waters Capital is Short St. Jude Medical.

Bloomberg reports the story and interviews Carson Block of MWR, and interviews Justine Bone, MedSec CEO. Both basically rehash what is found in the MWR report.

Star Tribune reports,

"Cybersecurity experts and physicians said they needed more information before taking any action. But the information in the report was specific enough that they’re concerned, and are seeking answers."

Local medical device data security expert, Ken Hoyme, notes that, “..nothing in the Muddy Waters report appeared infeasible."

On the day's trading, "STJ stock down more than 8 percent of its value within 90 minutes of the news breaking. The stock regained 3 percent of its value in the following 90 minutes, and closed the day down 5 percent, at $77.82."

August 26, 2016

STJ responds with an initial press release refuting MWR's claims. STJ makes a categorical assertion that MWR’s report is false and misleading. The press release does not include any rebuttals to any specific charges made in MWR’s report.

Star Tribune reports that FDA has joined the investigation into MWR claims, and that Homeland Security is also involved.

“At the present time, patients should continue to use their devices as instructed and not change any implanted device. FDA will provide updates as we learn more. In the interim, if a patient has a question or concern they should talk with their doctor,” FDA spokeswoman Andrea Fischer said in an e-mail Friday.

Although the Muddy Waters report used stark language to allege the risk to St. Jude heart devices, it acknowledged that the firm was “unaware of any imminent threat to patient safety.” To date, no malicious cyberattack against an implanted medical device has been documented outside of controlled experiments and demonstrations.

In other words, "everything’s okay because who would want to hack my medical device system?"

The LinkedIn MedSec group's initial post regarding the MWR report and includes some interesting comments.

Threatpost reports on the MWR report and offers a succinct description of the vulnerabilities described in the report:

Researchers say they were able to get root access to the Merlin@home devices thanks to sloppy security that included certificate reuse and sharing of SSH keys and static credentials allowing an unauthenticated user to log in to the affected system with the privileges of a root user.

Robert Graham, CEO of Errata Security and well known data security expert, opines on the MWR report and data security disclosures in general.

August 27, 2016

Very interesting thought piece by Ollie Whitehouse on LinkedIn, titled Cyber Security Vulnerabilities, Hedge Funds and Going Short – the value vulnerability equities. The crux of this piece is that there is value in the knowledge of data security vulnerabilities. For many years there have been offensive buyers (criminal hackers, state actors) who buy zero-day vulnerabilities. Over the past several years a new market has emerged made up of defensive buyers, manufacturers who pay ethical hackers to find bugs and disclose them to the manufacturer so they can be patched. Back in 2014, hactktivist Andrew Auernheimer, who goes by the hacker name weev, described a new model where value could be extracted from vulnerabilities.

“The strategy is short equities—like all short sellers, I am looking to publicize flaws in publicly traded companies,” he said. “However, instead of financial problems, I will be looking for companies with poorly written software that breach the implicit promise of safety that they give when they take data from their customers. When someone affiliated with our fund identifies negligent privacy breaches at a public web service, we will take a short position in that company’s shares and then tell the media about it.”

Sounds familiar, doesn't it?

August 28, 2016

Securities litigation law firm Rigrodsky & Long, P.A. announced they are investigating potential legal claims against STJ regarding possible breaches of fiduciary duties and other violations of law related to the Company’s entry into an agreement to be acquired by Abbott Laboratories.

Might the legal actions anticipated/encouraged in the MWR report become a reality?

August 29, 2016

MWR responds to STJ's press release of August 26, 2016. MWR offers some tit-for-tat commentary in response to STJ's assertions. One technical issue was detailed, in which STJ claims to encrypt the data communications protocol that MWR claims is not encrypted. According to MWR, STJ’s communications protocol uses a simple data mixing technique to address performance, not data protection. St. Jude Medical’s own supplier, Zarlink, refers to this as "whitening" rather than encryption. In MedSec’s opinion, this method doesn’t even come close to the most basic encryption protections expected to protect patient data.

Half of the response/report is a (very entertaining) Credibility Assessment, an analysis of the STJ press release by a behavioral analyst intended to reveal the relative truth or deception of the STJ press release. The analyst goes on to categorize portions of the press release as examples of Convincing Statements, Exclusionary Qualifiers, Perception Qualifiers, Borrowed Credibility and Diversion Narrative.

Regardless of who you believe is the most or least credible, MWR or STJ, the crisis communications strategy employed by STJ seems a mistake.

On the same day, MWR also released a video of one of their exploits, in which they claim to have crashed a STJ pacemaker. The video does show the researcher communicating with the pacemaker via a hacked Merlin@home device and injecting the pacemaker with data via software running on a laptop, also connected to the Merlin@home device. The video appears to be inconclusive as to whether MedSec is able to crash the pacemaker.

On the MedSec LinkedIn group, Shawn Merdinger notes that the Merlin@home remote monitoring gateways available for purchase on eBay dropped from 18 to 5 over the previous weekend. Shawn suggests this might mean that new researchers are working to validate the claims in MWR's report. Perhaps.

Financial site, Seeking Alpha, has an interesting story on the financial issues surrounding the MWR report and its potential consequences.

Patent litigator, Fish & Richardson PC, offers some interesting perspective:

For practitioners, this dizzying interplay of issues—cybersecurity disclosures, medical device hijacking, publicly-traded securities, high-stakes deals, and ethical hacking—presents a rich opportunity to study how judges and federal agencies will respond. Already, the FDA has announced that it would investigate the claims made in Muddy Waters’ report; the SEC can’t be far behind. Litigation, too, seems all but certain.

And this advice:

For publicly-traded companies of all walks and industries, this episode underscores the need for a swift response plan to mitigate the fallout from a similar disclosure, which could include a drop in share price, break-up of a pending deal, shareholder litigation, and even scrutiny from the government. At the same time, companies falling under this kind of spotlight need to take the utmost care in crafting a public response to ensure that no false or misleading statements are inadvertently made in the critical hours and days following such a report, especially while an investigation is underway and the facts are still fluid. Of course, a robust approach to implementing cybersecurity measures in all aspects of one’s network infrastructure and connected devices is always a foremost priority. But recognizing that no plan is foolproof—and that hackers, whatever color hat they’re wearing, are a motivated lot—companies can learn some valuable lessons from last week’s developments and prepare for the worst.

August 30, 2016

Courthouse News Service reports a class action suit was filed August, 26 that claims, "...pacemakers and other implanted heart devices sold by St. Jude Medical can be attacked by hackers to steal personal information and even harm patients."

[The patient] seeks certification of two classes: a national one, and one of purchasers from Illinois, where he lives, and restitution and damages for breach of warranty, fraudulent concealment, negligence and unjust enrichment.

His lead attorney Mike Arias, with Arias, Sanguinetti, Stahle & Torrijos, did not return a call seeking comment.

STJ issues another press release, this one in response to MWR's video of the day before. Lots of bluster, little substance.

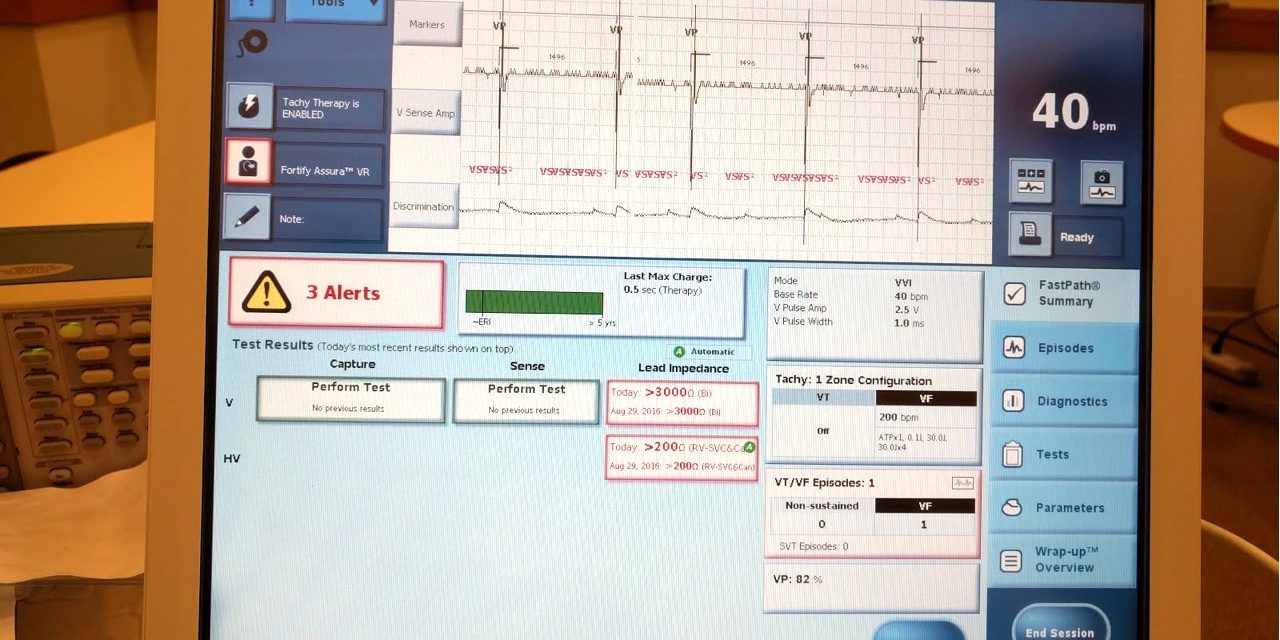

The University of Michigan Archimedes Center for Medical Device Security issues a press release describing how they recreated the indications displayed in the Merlin programmer that was included in the MWR report (that's the UM photo of the Merlin's screen at the top of this post). Kevin Fu claims that the pacemaker was not crashed in the MWR video and that the behavior MWR saw was the result of the pacer’s leads not being connected. It is not clear whether the UM team also attempted to actually recreate the attack described in the MWR report. Further, the University of Michigan press release is no more detailed and specific than the MWR report. None of the many other substantive issues that may have been validated (or ruled out) in the process of reproducing the Merlin display photo included in the MWR report are discussed.

This Star Tribune story touches on the MWR video, STJ response and the University of Michigan report on their attack. And here is another story on the same University of Michigan press release.

Finally, Kevin Fu publishes a blog post on the work reported in the previous University of Michigan press release.

August 31, 2016

Threatpost reports on reactions to the potential financial benefit that might accrue to MedSec as a result of their research:

Troy Hunt, creator of the cyber-breach service Have I Been Pwned? and author at Pluralsight said the precedent set by MedSec lays the groundwork for more alliances between research companies and profit-oriented investment firms.

Hunt believes the quid-pro-quo between MedSec and Muddy Waters could signal a new profit engine for cash-strapped research companies. “What would you as a researcher do if a short trader said let’s make a deal? The next big vulnerability you find, come to me first. I’ll take care of you financially,” Hunt said.

September 1, 2016

The Risky Business podcast includes an interview with Justine Bone, CEO of MedSec. Bone reported that MedSec is working with FDA and Homeland Security on the process of disclosing specifics of their research. They have not been contacted by STJ.

Another bit of news was how they got access to medical devices: MedSec entered into relationships with physicians to gain access to certain equipment (the pacemakers). MedSec is currently out of pacemakers; they bricked them all. Devices like Merlin@home were bought used.

The Register has a nice summary on theUniversity of Michigan Archimedes Center for Medical Device Security report of August 30, 2016.

September 2, 2016

This RealClear Health story delves into manufacturer responses to security breaches.

That marketing language, along with a blanket denial of the most specific of charges is in my professional opinion an indication that the company does not intend to address the issues raised, but instead, the reputational and share price fallout.

IEEE Spectrum has a story on the MWR report and the University of Michigan lab's work on validating the MedSec research.

It’s important to note that Fu has not yet tried to reproduce the hacks that MedSec claims to have pulled off: most notably, a “crash attack” causing an implanted device to beat at dangerously fast speed and another attack that allegedly drains a device’s battery. Fu says his team at the Archimedes Center for Medical Device Security is still investigating the claims.

September 6, 2016

Bloomberg has a story announcing, "A new way to bet against stocks is born." The story provides the best summary so far of how the MWR/STJ short may impact investment strategy into the future.

Whether the short succeeds or not, the unique partnership between Muddy Waters and MedSec has jolted the investment community and created a model for a new way to make money in the market: Find a company or industry that is adopting internet-connected devices, check whether the gadgets are hackable, place your trades and publish the research.

Of course, the adoption of the strategy above will depend on the perception of the relative success or failure of MWR's short. Another factor will be frequency of situations where the confluence of vulnerabilities, potential regulatory enforcement, and a situation like a pending merger to potentially enhance a short strategy.

September 7, 2016

Bloomberg has a 6+ minute video interview of their lead reporter on this story, Jordan Robertson, who gets into a discussion on potential long term impacts of the MWR/STJ imbroglio. Well worth having to sit through the 13 second commercial before the interview.

STJ brings legal action against MWR and MedSec. Discovery goes both ways; this should be interesting. You can download the complaint, filed this morning, here.

STJ's local paper, the Star Tribune, has more reporting, this time about STJ suing MWR, MedSec, et. al.

Another thought piece on monetizing software bugs from Lawfare.

September 8, 2016

The first reporting on the STJ suit against MWR that looks into the legal issues. The track record for these kinds of legal actions is discussed (and it does not appear to be good).

Speaking generally, white-collar lawyer Asaro said the guiding principle was that even wrong opinions could be protected, so long as they were made in good faith and the underlying facts were presented fairly. "Where people get into trouble is where they misrepresent the facts," Asaro said. "That's why these cases are so fact-specific."

Muddy Waters has courted controversy before with its criticism of companies whose stocks it bet against. Two targets of those comments, rice trader Olam International and bankrupt Chinese timber company Sino-Forest, sued Muddy Waters in Singapore and Canada, respectively. The cases were later dropped.

"St. Jude Medical now joins the ranks of Sino-Forest and Olam International as companies that have filed frivolous lawsuits against us for criticizing them," said Muddy Waters founder Carson Block in an email.

In a post on StreetInsider.com, cybersecurity expert Mark Lanterman refuted security claims by MedSec and MWR against STJ pacemakers, defibrillators and Merlin monitoring system. This is a second hand (or third hand?) report attributed to analyst Brooks West at Piper Jaffray regarding statements made by Lanterman during a "KOL call" (key opinion leader?). Without attempting to validate MedSec's research, Lanterman categorically derided the MWR claims as data security attacks that, "could not be replicated," and "unlikely."

As stated before, the only substantive assertions regarding the MWR claims will be those based on actual validation of the MedSec research. The FDA has disclosed that they are doing this validation with the help of Homeland Security.

September 9, 2016

In a Fox News interview, FDA repeated that the agency has undertaken a "thorough investigation" of the MedSec/MWR report. The spokesperson said that the investigation started in August after the MWR report was released. There was no reporting on when the investigation might be complete.

Electrophysiologist, MedSec board member and defendant named in the STJ defamation complaint against MWR and MedSec, Dr. Hemal Nayak, is quoted in an article on a meeting held with brokerage firm Jeffries.

"His [Nayak's] view was that when a device is put into Safe Mode it is an indication that something is wrong and MedSec showed it could remotely change the operating parameters of a device," analyst Raj Denhoy wrote in a note.

September 10, 2016

Fortune has thought piece on cybersecurity vulnerability arbitrage that asks way more questions than it answers. While the MWR report on STJ is the first example, this approach to monetizing security vulnerabilities was first articulated a few years ago. Not mentioned in the story are the key criteria that seem to be emerging from this situation for successfully conducting the kinds of profit taking on vulnerabilities described. The list in short:

- A "serious" vulnerability, a

- Regulatory framework that can be used to pressure the targeted manufacturer to lower stock prices (such as a third party to validate the vulnerability and force a recall), a

- Relatively high cost to acknowledge the vulnerability by the manufacturer (in the STJ case again, a lengthy ship hold and recall), and a

- Financial situation that makes the overall cybersecurity vulnerability arbitrage an attractive play (e.g., the Abbott merger enhances both the short opportunity and offers an opportunity to hedge risk).

Even though the genie is out of the bottle, it does not seem very likely that there will be many opportunities to exploit this short sell strategy. And with some data security remediation efforts on the part of potential target manufacturers, the number of future opportunities should fall.

One thing is clear from the MWR report on STJ, simply publicizing alleged vulnerabilities does not have much of an impact on the stock price.

September 13, 2016

Politico has a a story today titled, Cyberattacks have yet to hurt health care's bottom line. While interesting, most of the story deals with health care providers who have suffered data security breaches. The last quarter of the story gets into the STJ/MWR imbroglio.

The following excerpt shows why FDA regulations are so interesting (or frustrating) given the many variables that impact decisions and the relative opacity of FDA decision making.

The Muddy Waters report argues that because St. Jude hasn’t met certain conditions outlined in FDA’s guidance regarding cybersecurity maintenance of medical devices, the manufacturer will be forced to recall the devices and resubmit the changed devices for FDA approval.

But that argument isn’t necessarily true, says John Fuson, an FDA lawyer with Crowell & Moring. The FDA’s cybersecurity maintenance guidance documents present conditions that will assure enforcement discretion for manufacturers. But they don’t say FDA will recall products that don’t meet those conditions. The FDA guidance also says that in many instances, companies can tweak their devices for cybersecurity purposes without having to seek re-approval.

FDA takes action based on its perception of risks and rewards, Fuson notes. To recall St. Jude’s devices would mean forcing sick patients to undergo surgery to remove an implant based on a theoretical cyber risk.

But since FDA has expressed concern about the St. Jude’s report, the device-maker could end up being an interesting test case for the financial significance of cybersecurity for health care, he said.

"Enforcement discretion" is when the FDA choses not to enforce regulations against a manufacturer because 1) they think the manufacturer is responding to a situation appropriately, or 2) any resulting risk to patient safety does not meet a threshold at which enforcement is worth the effort.

One error in this story (and in the above quote) is that a recall would require the removal of implanted devices. This is a very unlikely extreme scenario for a STJ recall. Before these devices are explanted, a mitigation strategy would look at rewriting the devices' firmware (e.g., to fix any communications protocol vulnerabilities) first, and if that doesn't work, would likely direct physicians to turn off the pacemaker's wireless radio. Only a very small percentage of patients (if any) would be considered for explantation because their condition requires the day to day remote monitoring facilitated by the pacemaker's radio and Merlin@home.

The potential time frame of a recall is made up of a number of factors. Following the FDA Quality System is a requirement for any product development or changes, including security patches. Once development (or in this case, security fixes) are complete, then there is the potential impact of the time required for FDA approval. Should MWR's description of the state of the software in the Merlin@home device be somewhat accurate, the development phase of any fixes would likely be longer than any FDA approvals. Also, this example scenario with the Merlin@home does not include any potential impacts to software changes that might be required by the implantable devices, Merlin programer and Merlin.net network and server applications.

If STJ can go to specific software modules to apply security patches, it is likely no FDA approvals or clearance would be required, as described in this story and in the FDA's draft guidance document on postmarket cybersecurity. However, should STJ need to rewrite major portions or all of the Merlin@home device's software, because the software is poorly structured and organized (commingling the communications protocol throughout the software), FDA could require a review of the changes. Provided STJ's Quality System artifacts are complete and accurate, such a review could be as short as 3 months. If STJ stumbles with their submission, FDA review could take 6 or more months.

Once again, the bottom line is the accuracy of the MedSec/MWR report, FDA's ability to validate MWR's claims, and the FDA's perception on the severity of any resulting security defects.

Here is a more biased and inflamatory story claiming, Chance of St. Jude recall over cybersecurity threat 'practically zero,' analyst says. A stock analyst (with no disclosure on whether they've taken a position on STJ), touts claims allegedly made by, "two unnamed med-tech executives who have expertise in wireless technology. (One of those experts previously worked for St. Jude)." Levy claims it would only take STJ 1 to 30 days to make any fixes to their cardiac rhythm management system. Levy appears to be promoting an extreme best case outcome for STJ. Time will tell.

Levy raises interesting questions about the broader impact of the STJ/MWR imbroglio:

In addition, Levy said he doesn’t expect the spat to influence how med-tech companies incorporate wireless technology into their products going forward.

“For now the benefits and advantages of wireless data transmission greatly outweigh the cybersecurity risk," he wrote. "Nevertheless, the manufacturers and [Food and Drug Administration] should continue to raise the bar as it relates to improving cybersecurity of medical devices.”

The STJ situation may turn out to be an edge case, and thus not applicable for medical device manufacturers in general. And certainly, "the benefits and advantages of wireless data transmission greatly outweigh the cybersecurity risk." The long term takeaway for manufacturers should be to deal with data security early in the product development phase when such additions are at their lowest cost. Bolting on data security at the end of the design phase is ineffective and expensive. Rounding data security corners in product development clearly has costs, as the STJ situation will likely bear out, even if MWR's claims are not proven to be true.

September 15, 2016

The Risky Business data security podcast has another scoop on the STJ/MWR imbroglio with the first interview with a legal expert on the intersection of data security and securities law. (The first tech press scoop was Patrick Gray's interview of MedSec CEO, Justine Bone in episode 425, also noted above.)

Risky Business contributor Brian Donohue spoke with Cahill law firm partner Brad Bondi about the suit St Jude Medical has brought against MedSec and Muddy Waters over the short-sell of the medical device manufacturer's shares.

The interview starts at 43:45 and lasts for about 20 minutes. The interview is focused on the suit by STJ against MWR, but also looks at other potential legal issues. Here are some of the highlights:

- The case will come down to whether MWR had a good faith factual basis for the accusations made in their report, or whether the report is false. Another key consideration is whether the research findings are fairly presented.

- There will be a discovery phase where each party gets access to documents and deposes the other party's principals.

- There is a line between permissible short selling and what is not permissible. As long as MWR has a good faith factual basis for the accusations made that drove the short, there should be no short selling legal issues.

- Can MWR's data security research be considered material non-public information that would lead to insider trading? Likely not.

- Could MWR have some terms of use vulnerability related to how they accessed the STJ devices used in the research? Generally speaking, no.

- Public companies are supposed to disclose risk, and cybersecurity can clearly be a risk with a public company's products or services. This gives rise to situations where securities law and the first amendment intersect. One can say what one wants about a company or their products, provided there is a basis for the statements. Much like when someone cries, "fire!" in a crowded movie theater, panic can ensue. In the stock market, information can also cause a panic resulting in the sale of the company's stock. Now the question becomes, did those that disclosed the information have a reasonable basis for the statements that were made? Factual basis, word choices and background all matter.

- Very very few of these types of lawsuits go the distance to get resolved at trial; most are settled.

One question that was not asked in the interview is what impact a recall decision by the FDA would have on STJ's suit. Should the FDA chose not to enforce a recall on STJ, it would seem harder for MWR to present their report as a good faith factual effort. Conversely, is it game-over for STJ if the FDA forces a recall?

It should be noted that MWR has been sued by the targets of many of their past reports and short sells. All of the suits were dropped or settled; none went to trial. Many of their past report accusations were born out, some after lengthy investigation, and contributed to successful shorts.

September 16, 2016

The story, Security vulnerabilities: You don't need a breach to face regulatory scrutiny, the authors point out how data security vulnerabilities are impacting companies, regardless of whether there has been an actual breach or not. The STJ/MWR imbroglio is mentioned as an example of vulnerabilities impacting STJ and the market in the absence of a breach. The authors advise:

In light of the growing trend of regulatory action and litigation resulting from the mere existence of cybersecurity vulnerabilities in products and services, and even from inadequate policies in corporate cybersecurity programs, companies may want to focus their efforts beyond just preventing actual data breaches and become more proactive in identifying and remediating vulnerabilities.

September 21, 2016

A story about the growing trend of measuring cybersecurity as part of an investors’ due diligence process reports (emphasis added):

Just days after St. Jude Medical’s stock was crushed on the New York Stock Exchange, one of St. Jude Medical’s investors reached out to Jason Syversen, a former DARPA program manager and the now CEO of Manchester, NH.-based Siege Technologies, FedScoop learned. Siege Technologies describes itself as providing “offense-driven defensive cybersecurity solutions."

“They are worried about the report and future bombshells,” Syversen said.

Over the last several weeks, this investor — who Syversen declined to name — is also speaking with other offense-oriented cyber firms in an effort to validate MedSec Holdings’ claims.

“The idea is to prevent surprises like this again,” said Syversen.

This is the first reported case where a STJ investor is seeking to validate MedSec's research themselves in order to gauge the veracity of the claims made in MWR's report. It seems that most investors are simply seeking out experts for their opinions on STJ and the MWR report. In situations like this, nothing counts but validation of the MedSec research.

Private equity investors are responsible for doing their own research to make investment decisions. Likewise, public companies are required to disclose risk to inform investors' research. Historically, this risk is usually limited to financial performance and company operations. Traditional forms of risk disclosure do not address data security, resulting in a lack of data security information for the investor to use to make an investment decision. Situations like the STJ/MWR short provide an example of how the paucity of data security information results in potentially important risks not being disclosed, and creates investment opportunities for diligent researchers.

Surprise: FDA CDRH lists data security as one of 10 top regulatory science research priorities for 2017 (pdf).

August 31, 2017

A year after the Muddy Waters' initial announcement brings news on what may be the last of the St Jude patches of security vulnerabilities. From this Ars Technica story (here's the FDA recall notice):

Talk about painful software updates. An estimated 465,000 people in the US are getting notices that they should update the firmware that runs their life-sustaining pacemakers or risk falling victim to potentially fatal hacks.

Let's review. The battery depletion claim? Confirmed. Merlin system wide vulnerabilities? Confirmed. Negligent data security practices and lack of follow up on vulnerabilities? Confirmed.

At this point, it's pretty clear that everything Muddy Waters claimed about the St Jude vulnerabilities was true. The only thing that didn't happen was that FDA did not issue an expensive recall that would have leveraged Muddy Waters' short of St Jude stock.

The Christian Science Monitor has a nice summary article that reviews the big picture issues, many of them disappointing. Also, here's an interesting interview with Justine Bone of MedSec from January 2017 at the S4 ICS Security Conference on the St Jude disclosures and MedSec's work with Muddy Waters.

Was the FDA's decision not to issue that recall a judicious balancing of actual versus theoretical risk (the theoretical being much bigger than the actual), an example of regulatory capture, or both?

And what of St Jude's defamation lawsuits they leveled against Muddy Waters, MedSec and other principals? I looked on Pacer today and found that the last filing in that case was 8/23/17, right before the big recall reported in the Ars Technica story. I expect that this bit of brinkmanship on the part of St Jude will cost them too.

All told, what do you think this debacle cost St Jude/Abbott? In direct costs, I'm guessing $100 million for all the unplanned R&D and time required to review and revise policy, training and dealing with FDA. Oh, and don't forget the cost to settle the defamation suites. Any lost market share would be on top of that. I can think of at least 460,000 people who won't be too keen on implanting a St Jude device any time soon.

Photo credit: the photo at the top of this post is courtesy of the University of Michigan Archimedes Center for Medical Device Security. Copyright the University of Michigan Archimedes Center for Medical Device Security.

Recent Comments