When I had a chance to talk with some FDA officials involved in software compliance, we talked about secondary alarm notification systems and how they fit the FDA's regulatory framework. It was a very interesting conversation. With a finite budget and human resources, the FDA has a whole laundry list of issues that do not reach the threshold of proactive enforcement; secondary alarm notification has yet to reach that threshold. If (or when) a situation arises that breaches this threshold they will enforce the regulations.

According to the FDA folks I talked to, the 21 CFR regulation does not make (nor allow for) a distinction between "primary" and "secondary" alarm notification. Any system "labeled" as a means for alarm notification is a medical device per the regulation. The term "secondary alarm notification" appears to be a term of art created by industry, rather than a regulatory distinction.

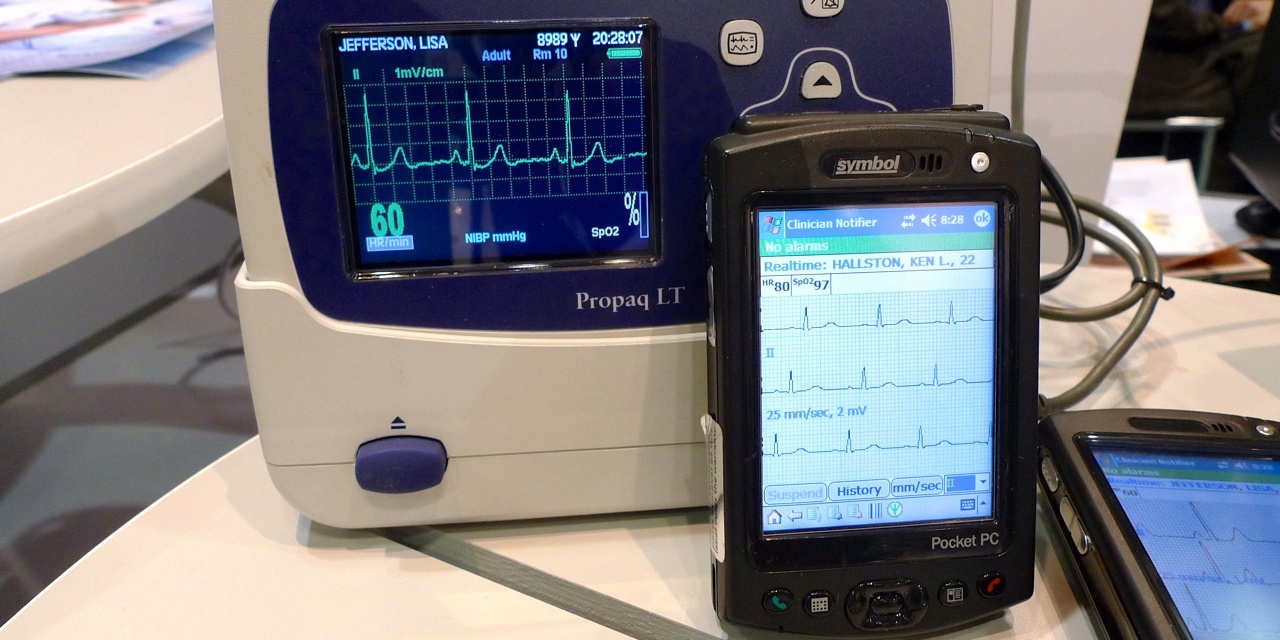

In the 1990s Philips and VitalCom (acquired by Data Critical, acquired by GE) brought to market nurse-carried alarm notification using wireless pagers. These pagers displayed both alarm text and a sample waveform. Paging systems are not a closed loop system and adverse events resulted when alarms were never received on the pager. The FDA's involvement in these reported events resulted in a change in product labeling and creation of the term "secondary alarm notification" by vendors. Over the last few years, several vendors have shown nurse-carried alarm notification devices using closed loop WLAN systems, based mostly on PDAs. With the exception of Baxter's PDA for their smart pumps and Cardiopulmonary Corp's products, no other vendor has yet to offer a released product of this type that is covered by a 510(k) with an intended use that includes alarm notification.

One might reasonably ask, "If the buyer knows the distinction between primary and secondary alarm notification, what's the harm?" First off, there are hundreds of secondary alarm notification systems installed in hospitals; secondary alarm notification market penetration is probably just over 10 percent. Based on the capabilities of some of these installed systems, or how they are used, one could reasonably question their safety. (You can find another answer here.) With increased pressure on hospitals to improve patient safety the need for alarm notification that extends beyond the bedside device or central station grows. Market demand for improved alarm notification also exists because higher acuity patients are being cared for outside traditional critical care areas where the endemic nursing shortage sometimes stretches nurse to patient ratios. These more acute patients are frequently under more aggressive therapies (delivered by infusion pumps and ventilators) necessitating greater surveillance (telemetry or multi parameter patient monitors). The impact of these changes on alarm responses has not gone unnoticed. These "secondary" alarm notification systems can offer many advantages over traditional central stations or local device-based alarms.

If improved alarm notification was simple and straight forward, they would be included in vendor's 510(k) intended use statements and this would be a non-issue - but it neither simple nor straight forward. Medical device vendors must reach beyond their embedded systems business models and venture into the land of general purpose computing systems. Health care IT vendors must do the opposite, and consider crossing the regulatory hurdle mandated by 21 CFR. And of course hospitals want solutions that will fit into their IT environment, and caregivers are not interested in carrying more than one alarm notification device.

Vendors need to consider new approaches to improved alarm notification that truly meet market requirements (even the ones they'd rather not meet). For years, vendors have relied on the high level of care provided in operating rooms and critical care units to ensure the safety of local alarms. (If the efforts of CIMIT's Operating Room of the Future are any indication, improvements are needed in those areas as well.) As more patients are treated and monitored in more general care areas, the need for improved alarm notification will continue to grow. Patient safety and alarm notification could be an inflection point resulting in major changes to the medical device market with new players grabbing major market share, and some vendors seeing their products becoming commoditized.

Can hospitals buy these types of systems without assuming undue risk associated with "off label" use? The short answer is yes. What is needed is a needs assessment, vendor selection, and implementation process that ensures the purchase of a system that can be used safely in your environment. Hospitals following a documented process that assures patient safety should be reasonably protected in the event of a sentinel event that involves a secondary alarm notification system. If your hospital has a secondary alarm notification system in use, an audit of the system's capabilities and how it is being utilized should be done. Of course, it is only in using regulated medical devices in accordance with the device's intended use that a hospital's liability risk will be at the absolute minimum.

Recent Comments